TO an outsider it would probably seem a strange question to ask, but if you found yourself in Harry Jones’ shoes it would likely become quite pertinent. Shortly before his execution for multiple cases of attempted murder in the late 1800s, Jones turned to hangman James Berry and calmly asked: “Is this going to hurt much?”

Berry, who had dispatched 136 murderers to meet their Maker, was slightly taken aback. But gathering his thoughts replied: “Hurt you? You keep up brave like a Christian and I won’t hurt you, Jones.” To which Jones responded: “I’m ready then.”

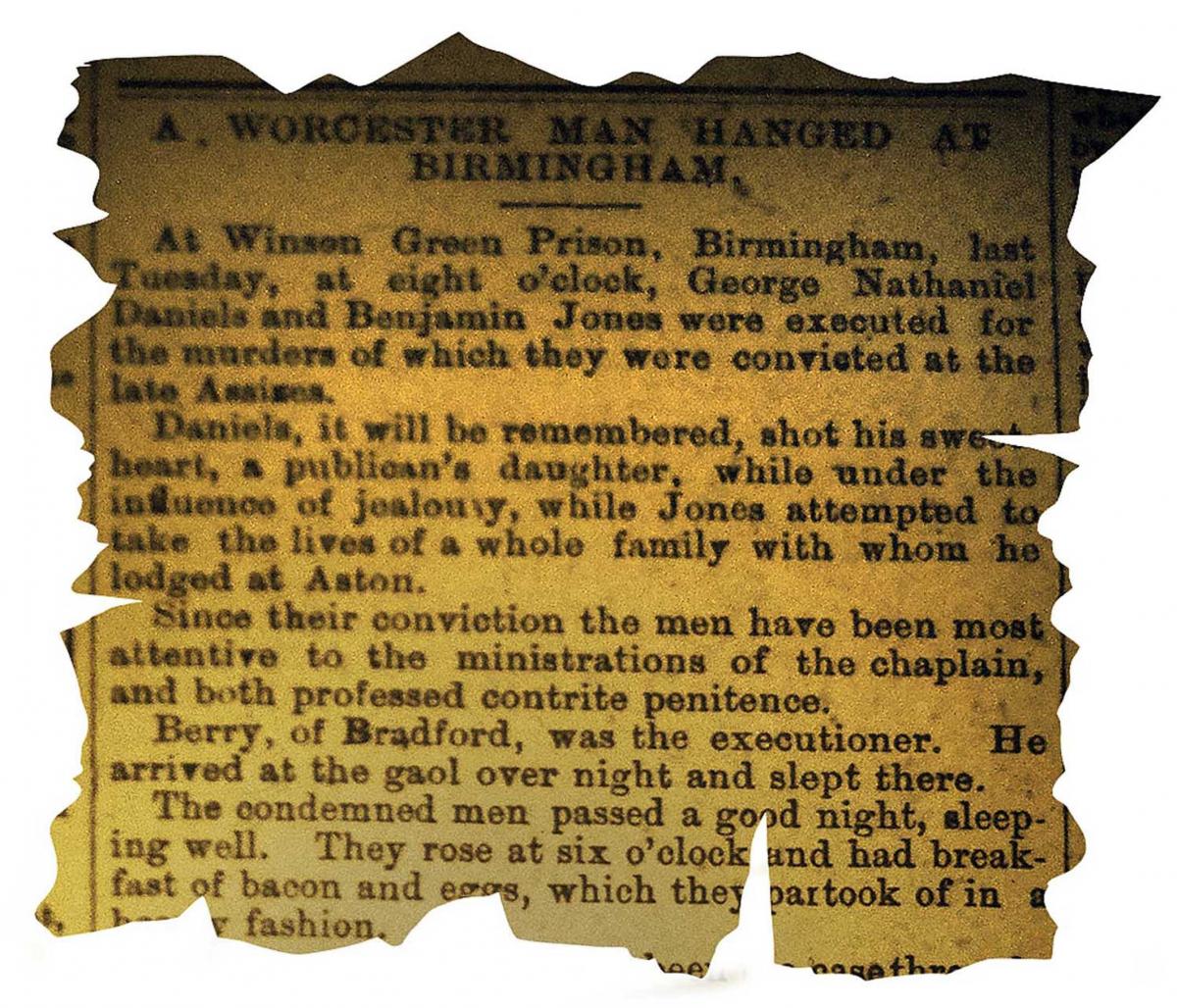

Beside Harry Jones on the scaffold in Birmingham’s Winson Green prison that day stood Worcester born and bred George Nathaniel Daniels. The couple had struck up a close friendship while awaiting execution on the jail’s Death Row and Berry himself went on record as saying that during his five years as an executioner he had never met two men “who died so firmly”.

Daniels’ conviction was for the murder of his girlfriend Elizabeth Hastings. He was well known and still fondly remembered in Worcester as a very presentable young man around town, even though he’d been living in Birmingham for some years, Daniels’ father had kept the Angel pub in St John’s, although not always strictly according to the law. His tenure being chequered with a few out-of-hours charges, before he’d given up the inn and set up as a farmer in nearby Lower Broadheath.

The Daniels brood stretched to four sons and two daughters, all still living in Worcester with the exception of George, who married a Birmingham girl in 1883 and had two children, Bertie and Annie, in quick succession, before tragically, three years later, his wife died. Still grieving and reported to have been a kind and affectionate father distraught by the tragic circumstances, Daniels’ two children came back to live with his mother in Broadheath and an aunt in Bromyard, while he continued to live in Birmingham where he’d held down the job of porter at a stationery firm for the past 14 years.

In June 1887 George Daniels picked up with pretty 21-year-old Elizabeth Hastings, who still lived with her parents at their pub the Golden Elephant in Birmingham’s Castle Street. Their association began after Daniels befriended her father, who also ran a sideline as a bookmaker. This became the start of Daniels' downfall:. Grief over his wife and prolonged absence from his children set Daniels on the unaccustomed road of general drunkenness, accompanied by a crippling catalogue of gambling losses.

In a fit of drunken depression brought on by fears that Elizabeth, affectionately known as “Pem”, was about to break off their engagement – she arrived two hours late for their final date – Daniels shot her with a revolver at near point-blank range. However, he later said he recalled nothing of the incident, adding in a letter written to his employer from his condemned cell: “I don’t know whatever made me do such a dreadful thing. Nothing else but the cursed drink, for my dear Pem did not harm me in the least. She never did. She always did all she could for me. If only I had been ruled by her I should have been worth lots of money now, but my poor dear soul, she is dead.”

At his trial in Birmingham it came out that George Daniels had inherited his father’s excitable temperament and that he’d attempted suicide on the death of his wife and was now subject to “excitability” and fits of depression. In a letter to his brother John, who lived at Belle Vue Cottage in Northwick Road, Worcester, he admitted the previous year his black turns had become more frequent and he feared he was losing his mind. It also emerged his father and an uncle had also attempted suicide at some stage.

In another letter to Worcester, he wrote: “As true as God is my maker, I do not remember going into the house on Saturday night. I hope God will forgive me, as I do everybody else. God help me in my sad, sad trouble’.

Although he’d been living in Birmingham, Daniels still viewed himself as very much a Worcester man, visiting his old haunts on a regular basis and even briefing Worcester solicitor Albert Halford to handle his defence, who in turn retained Mr Young QC to conduct the case.

With the guilty verdict, Halford organised a petition for clemency which in just a matter of days attracted 8,000 signatures. But it was to no avail. On August 25, 1888 he received notice that the Home Secretary “…regrets he had not been able to discover any sufficient grounds to justify him in advising Her Majesty to interfere with the due course of the law.”.

So the once popular Worcester lad, George Nathaniel Daniels was hanged at Winson Green in a double execution three days later, at eight o’clock on the morning of August 28.. It was quick and according to the hangman, it didn’t hurt.

lBased on a case in the new book Suspended Sentences by Worcester author Bob Blandford, due out later this year.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel