IN the 1960s the Beatles and the Rolling Stones played concerts in Worcester, attracting huge crowds. Flash back 100 years and the visits of Thomas Marwood and James Berry caused much the same reaction.

Except Marwood and Berry were not in the city to entertain, they were here to kill.

Public hangings were at the sharp end of life in the 1800s and the pair were among the Official Executioners of their day, their job to see-off the constant stream of felons, rogues and ne’er-do-wells who had been sentenced to forfeit their lives for the crimes they had committed.

The gruesome event was usually held at Worcester County Jail in Castle Street, the venue to which the populace flocked in its thousands.

The prison opened in 1814 and for its first 50 years the Governors – John Nelson Lavender followed by his son-in-law Ben Stables – chose the hangmen from the ranks of conscience-free Worcester men willing to do the deed in return for little more than beer money.

But when too many hangings went hideously wrong. either because the rope was too short, leaving the condemned man to strangle to death, or too long in which case he was decapitated, the Home Office took control by circulating its own list of approved executioners.

The first was Londoner William Calcraft who is said to have loved Worcester and spent the morning of the six executions he conducted here walking on Pitchcroft, where he was followed by an adoring crowd of fans.

In his time Calcraft carried out 450 hangings, although not all went entirely according to plan. His memoirs outlined the occasions he was required to go down below the trap and pull on the prisoners’ legs in order to speed-up their death.

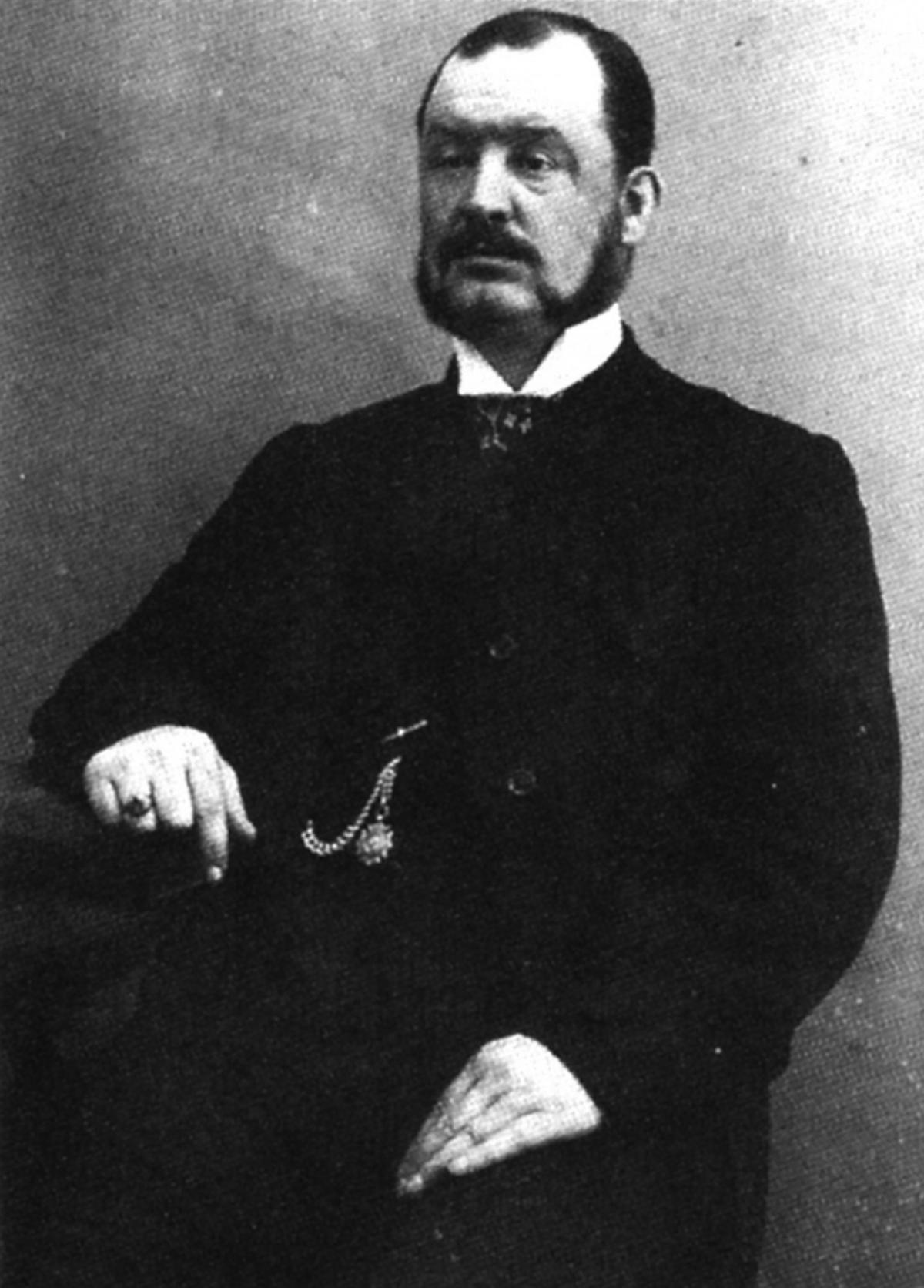

His successor at Worcester was William Marwood, a cobbler by trade, well read and educated, and he is credited with improving the hanging process by introducing the first Table of Weights by which the required length of rope was calculated according to the prisoner’s height, weight and age: typically, a 14-stone man would get a 5ft 1ins drop, an eight stone woman would drop 8ft 6ins. Marwood hanged a total of 179, including eight women, and a popular ditty of the day went: “If Pa killed Ma, who’d kill Pa? Marwood’!”

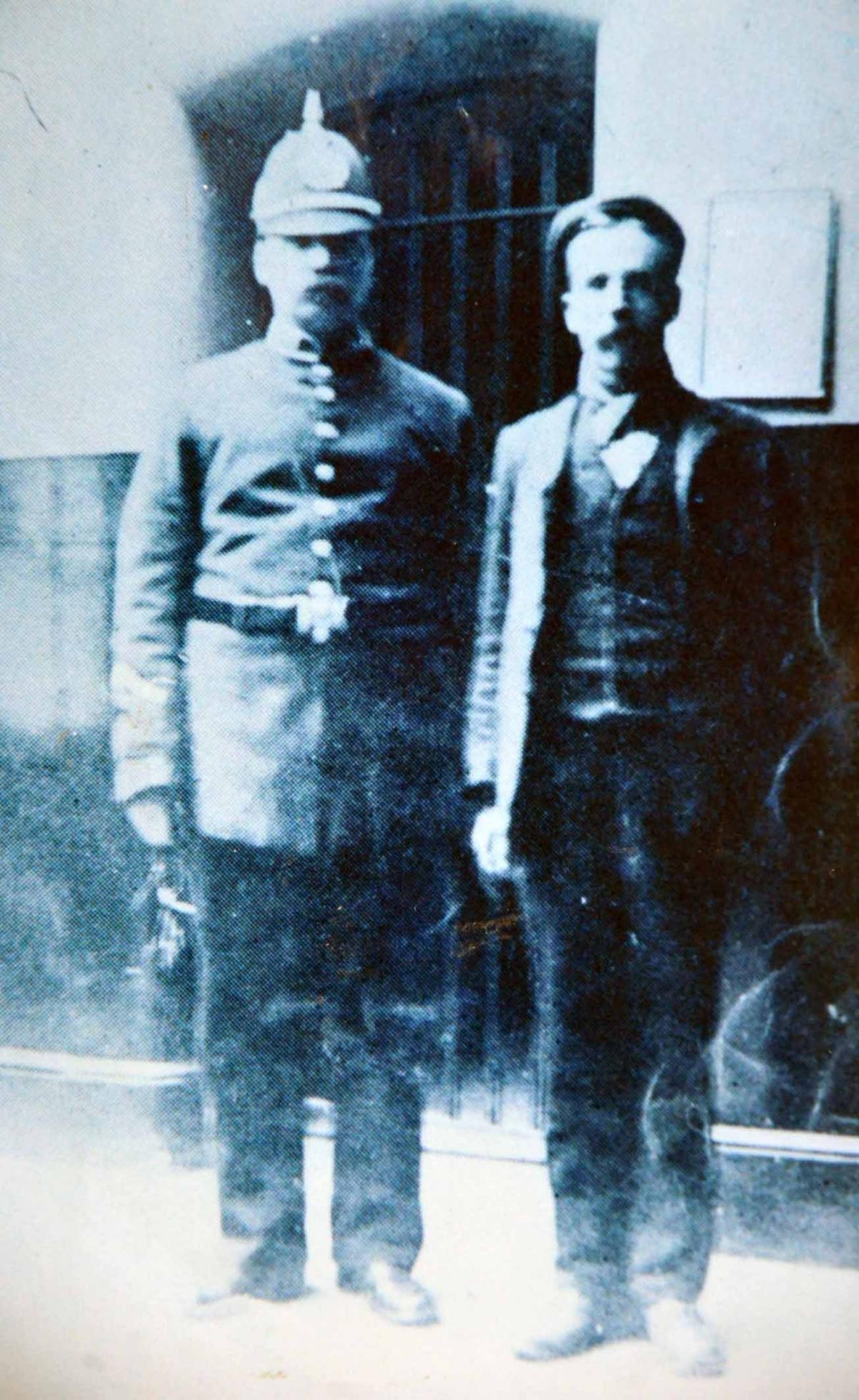

In 1884 he was succeeded by his friend and assistant, one-time Yorkshire policeman James Berry, whose entrance into and out of Worcester was met with huge crowds, all eager for a chance to mob their hero.

Many a local man bragged he’d carried hangman Berry’s black bag to (or from) the station containing the actual rope which had been used to hang dozens of prisoners.

Berry learned a lot from Marwood, but clearly hadn’t acquired his tutor’s sense of detail and when, on Whit Monday, May 25, 1885, he hanged the killer of Worcester County policeman James Davis, Moses Shrimpton’s head was ripped clear from his body as the 9ft drop he’d calculated based on the killer’s 10 stone weight had failed to take into account the condition of the 66-year-old farm labourer’s skin and muscle tissue.

Though James Berry went on to conduct three more executions in Worcester, he was already out of favour and was sacked. By now a sad and regretful drunk, he committed suicide not long after, aged 61.

His role was taken by ex-Sunday school teacher, wrestler, miner and pub singer James Billington, for whom being hangman was a family affair. Three of his sons, Thomas, William and John, all following their father into the “profession”.

Billington was followed by a name that has since become synonymous with the art of execution – Pierrepoint. This was ex-butcher Henry who’d been apprenticed to James Billington and whose brother Thomas and possibly even more famous son Albert were also executioners. But just as controversy surrounds the role of executioner, the individuals themselves were not above suspicion, mistrust and dissent.

Thomas and his assistant John Ellis – the two often reversed the roles – disliked each other with a vengeance, each accusing the other of being a drunk and a liability in the job.

In one notorious incident they swapped punches in front of a shocked governor and party assembled to witness an execution! John Ellis, a former Rochdale hairdresser, went on to conduct the last execution at Worcester Jail before its closure.

The condemned man was Chinaman Djang Djin Sung, only 4ft 11ins tall, who had been convicted of the murder of another of his countrymen, Zee Ming Wu in 1919.

It was reported that only 20-30 people stood in silence outside the prison during Sung’s execution, in contrast to the crowds of up to 7,000 which had filled Castle Street in earlier years. Though tiny, Sung was not the shortest man to be hanged at Worcester. That distinction belonged to Robert Pulley, who murdered 15-years-old Mary Ann Staite at Drakes Broughton in 1848. He measured a mere 4ft 8ins and his coffin was just three inches longer.

John Ellis also ended his days by suicide. He attempted to shoot himself in 1924 and failed but eight years later was successful, slashing his throat with a razor in 1932, aged 57.

In his time Ellis hanged 203 people including Doctor Crippen, Frederick Seddon, Sir Roger Casement and Edith Thompson.

Worcester prison was closed in 1922, but parts remained standing for many years and were used by furniture makers Rackstraws.

The area fronting Castle Street became motor dealers HA Saunders and then County Furnishings. It is now the Art House of the University of Worcester. So if students find a ghost sitting among them one day, they’ll know where it’s come from.

l Information from Bob Blandford’s up-coming book “Suspended Sentences, the long and short of a century’s executions at Worcester Gaol” due for publication next year. Bob’s previous four books, on old Worcester pubs and Worcester City Police, are all local best-sellers and he can be contacted direct at: bob.backenforth@worcester-pubs.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here