A WORCESTER man who experienced one of the world’s worst ecological disasters has reflected on it 35 years later.

Tom Piotrowski, who grew up in Poland, was a child at the time of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, which happened 25 years ago this week. Mr Piotrowski has looked back on how he experienced things from just over the border from where the disaster happened in Ukraine.

He said: “Whenever I hear the excitement in voices of people- work colleagues or friends- talking about visiting Chernobyl, I don’t share their enthusiasm. Yes, I am interested in history, but I also lived through that bit of history in the neighbouring Poland. It wasn’t exactly a fun experience.

“Confusion, fear of the unknown, inability to see that menacing and deadly radioactive cloud that all the adults were talking about were the prevailing emotions then and are still vivid memories now.

“I recall being scared and confused. As a child, I was grateful to have calm and reassuring presence of my parents who were telling me that everything will be all right. As kids, we taught to pray but we probably prayed more during that time.

“I recall joining my school mates at the starting point of the annual march to mark the International Worker’s Day. As an adult looking in retrospective, I can’t help but recall those marches in the context of what’s happening now in North Korea.

“Perhaps we Poles had a little bit more freedom to be cynical about it all. For instance, I never forgot my dad telling how the workers in the local cement factory had to paint grass green because an important Communist Party apparatchik was due to visit prior to the march. Grass in and around our town was covered in a grey powder from the chimneys of the cement factory. Ridiculous but true. Better filters appeared later.

“We already had received the news that something serious and dodgy happened in the neighbouring Ukraine. To give you an idea, we grew up in the place where to get to Lviv in Ukraine was probably quicker than to get to the capital city of Warsaw. Chernobyl wasn’t much further than the Baltic Sea from where we lived.”

On April 26, 1986, engineers at the Chernobyl Nuclear Plant were conducting a routine test of one of the plant’s RBMK-1000 nuclear reactors.

Due to human error, two explosions threw a huge amount of nuclear material, more than four times the radioactive strength of the Hiroshima bomb, over the surrounding area. With information tightly controlled, a huge clean-up operation was undertaken by Soviet authorities, with the truth about the faulty reactor fuel-rods being kept a secret for a number of years. The official Soviet death toll has remained at 31 ever since the disaster, the estimated number of people affected by the radiation is in the hundreds of thousands.

Mr Piotrowski added: “In the Communist Poland, where the information was strictly controlled, the first unofficial reports of the radiation but without full understanding of its source appeared only several days later despite the alarming readings at the radioactivity measuring posts, all over the country but particularly high in the northeast.

“The Soviets were not forthcoming with the information and many people in Poland learnt about the source of the radiation from illegal broadcasts of the Polish section of BBC World Service. We marched and waved our little flags but were probably keener on ice-cream and football after the ceremonial precession was all done. We stood at the small central marketplace in our little town of Ozarow and listened to predictably bored and incomprehensible party officials.

“But instead of being marched to a local ice cream booth by my mother, we all went to our local surgery. A massive queue of kids and their parents formed on that hot and sunny day.

“Small shot glasses of Iodine were waiting for children and adults alike. The smell and taste were awful, and I wasn’t sure what to expect afterwards.

“The fear factor was probably intensified by the fact that we couldn’t see the danger that this antidote was meant to prevent. I felt disgusted and mildly invincible against that unknown enemy radiating across the border form the east.

"The tragic irony of those marches was best appreciated with the shortages of fresh produce and groceries in the shops, as we were ordered by our schools and employers into the streets and made to march in support of ideology imposed on my Poland 40 years earlier.

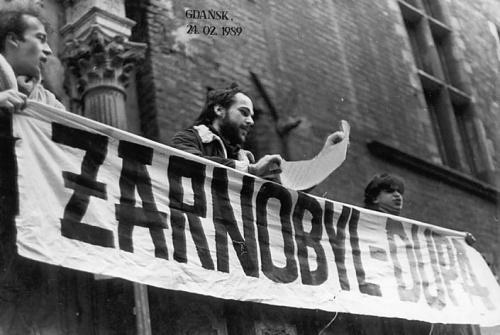

"As a result, Poland's ambitions to build its own nuclear plants have been put on hold and haven't been reactivated until now. The nuclear plant project in Zarnowiec was shut down in 1990. Poland has been wedded to the carbon emitting coal plants for decades to follow and that legacy has sadly prevailed to this day without sufficient investment in the renewable energy.

"The health effects of the radiation on the population, prevalence of new forms of cancers and swift but also desperate public health action of the otherwise oppressive government remain the subjects of study for historians.

"It wasn't the first time I felt that something undefined and yet lethal was threatening my family and our way of life. The first time I felt that feeling was in 1981 when the mentioned above Martial Law was introduced to 'protect us from invisible enemies of state'.

"Atrocities were committed then, and the Communist regime's brutality exposed in after the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989.

"All I recall was the snow, tanks and military personnel driving through our small town in south-eastern Poland and heading somewhere where that invisible enemy must have been.

"I'm grateful for the advances of science and for vaccines in the case of Covid-19 but I am wary of the dangers that the nuclear energy poses to our environment and to the population.

"Are we ready to react swiftly and decisively in the face of mortal danger?

"The Chernobyl disaster was caused by a human error and outdates technology.

"Our current safety rests with the complex and sophisticated software which protects much safer, in theory, nuclear reactors. However, are the software errors unheard of and uncommon? Sadly, they are not.

"That's one of the reasons why de-escalation of the nuclear arms race and alternatives to even the safest nuclear plant technologies have to be at the forefront of our thinking when we mark this 35th anniversary of the worst nuclear disaster in the history of our civilisation."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here