STANDFIRST:

In the second of a series of features about the Great War, Faith Renger of Malvern Museum explains how the conflict affected local schools.

SEVERAL primary schools had to cope with the loss of their young male teachers during the conflict. The record book for Malvern Parish school reported on December 2, 914 that "Mr W A Westwood terminated his duties today until termination of War. He joined the Devon Rifles for service abroad". He probably survived the war.

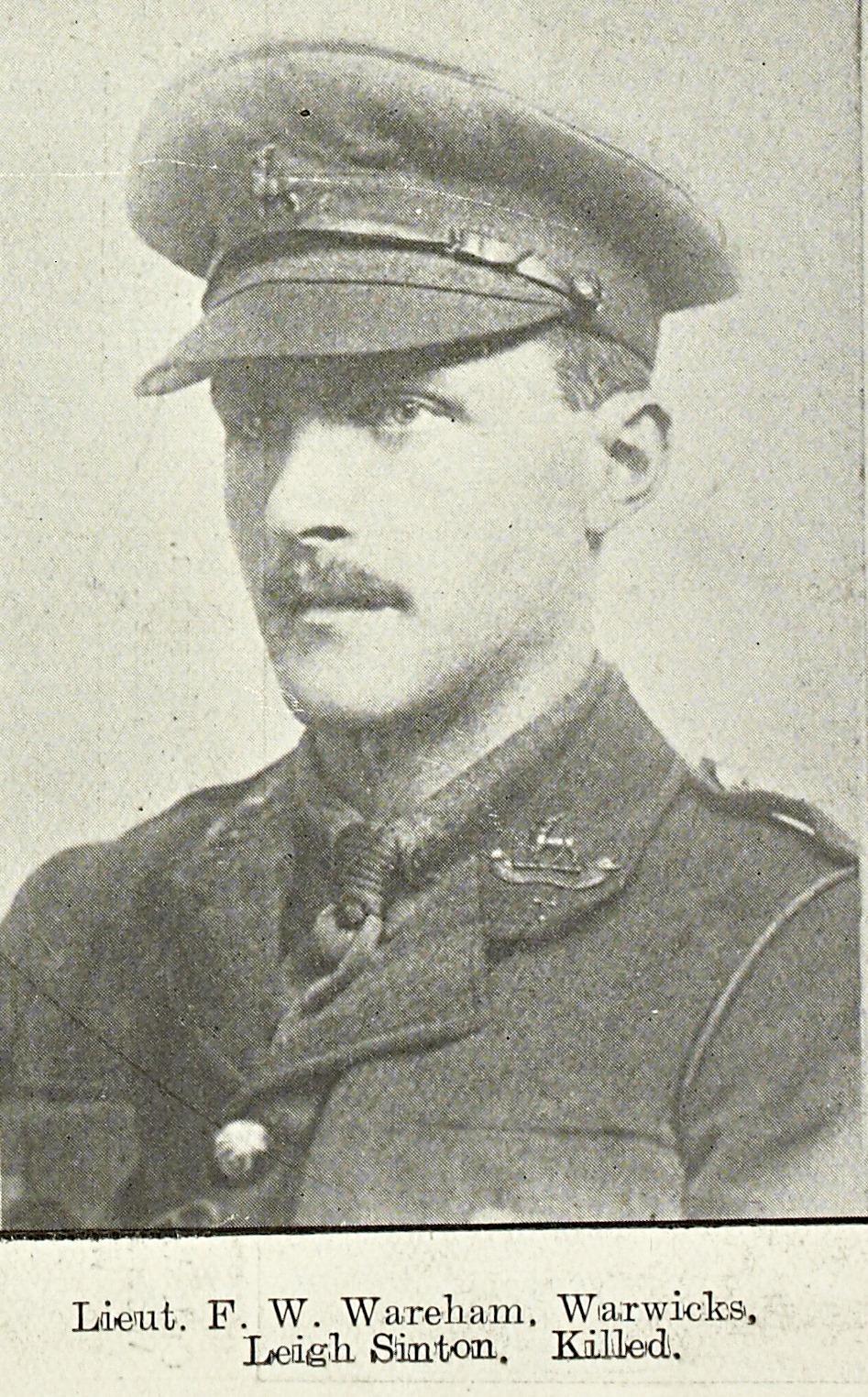

Others were less fortunate. Frederick Wareham was a student teacher at Somers Park School before the war. He was a lieutenant serving with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment when he was killed during the opening day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

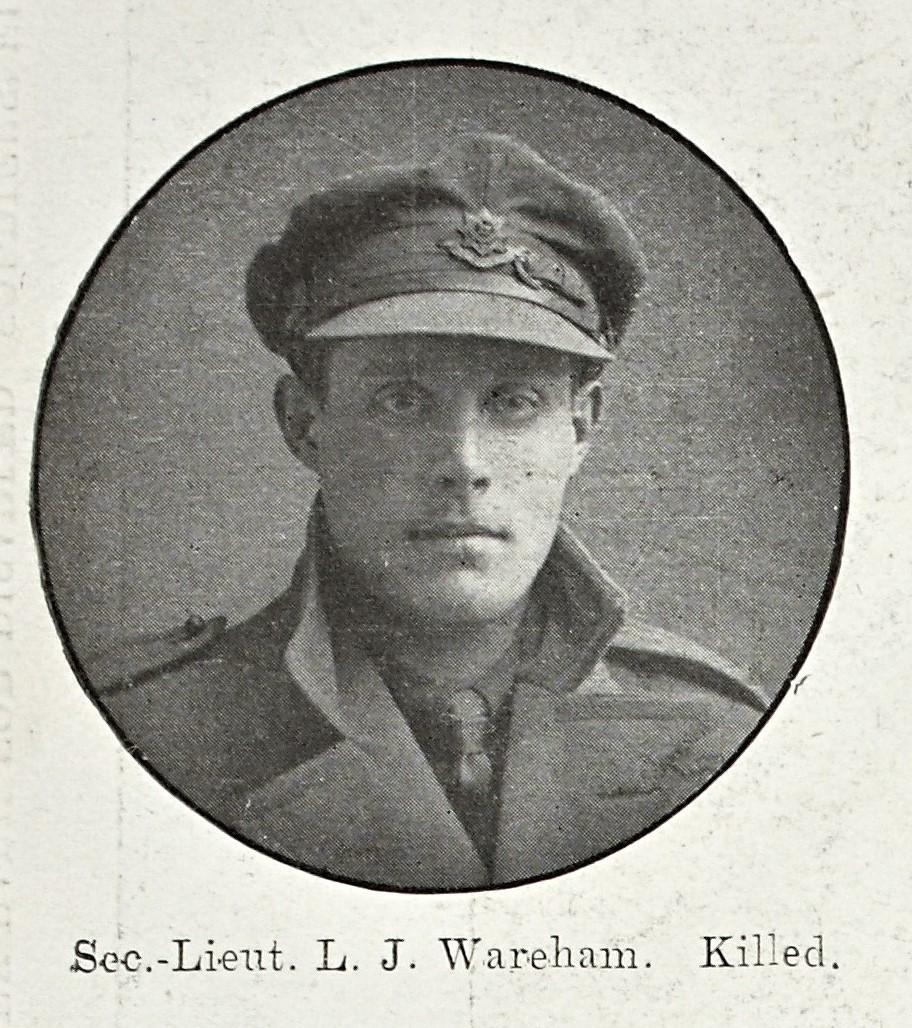

His brother Laurence had taught at Malvern Link School and he too made the ultimate sacrifice in the same battle just three weeks later.

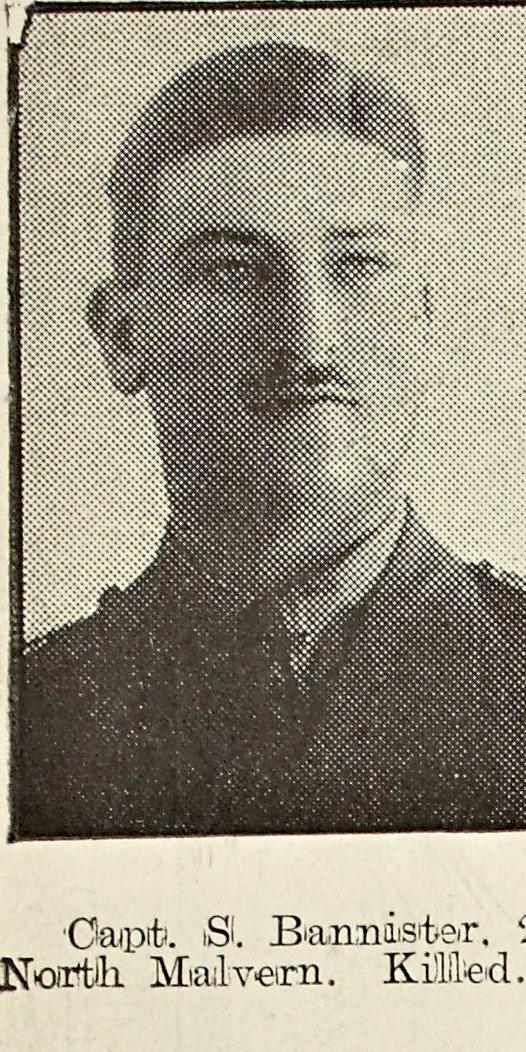

Samuel Bannister was employed at North Malvern and he and his brother both volunteered at the outbreak of war. Samuel Bannister fought with the Worcestershire Regiment and took part in campaigns in Gallipoli and the Somme. He was killed in 1917.

An assistant master at St Cuthbert's school in Worcester Road had been a member of the local Territorials before the war. Second lieutenant Arnold Batho lost his life serving as a signaller with the Middlesex Regiment in September 1916. He was 25.

School life was affected in other ways. School children were behind many worthwhile fundraising efforts such as collecting vegetables for the large number of Belgian refugees who had escaped to Malvern.

In December 1914, pupils from Malvern Link School were able to send a sack of potatoes, onions, carrots, parsnips, beetroot, celery, greens and turnips to the Belgian hostels. West Malvern Girls and Infants School collected a further 46½ pounds of potatoes, and a similar amount of other vegetables.

Malvern Link School pupils were also busy making and collecting 70 pairs of socks, six shirts, 12 body belts, 16 handkerchiefs, a pair of mittens, soap and laces. In addition they raised £1 for chocolate, 6s 6d for cigarettes and 15s 6d for the Princess Mary Christmas tins. In the same article from 1914 it was reported that 116 old boys of the school were serving in the army and navy.

Meanwhile, North Malvern School pupils were engaged in similar efforts, sending a large consignment of home-made socks, cuffs, mittens and scarves to various regiments. In many cases the children provided their own wool.

By the end of 1914, the children had been joined by a number of Belgian children who were taught in a school especially set up for them in Holy Trinity Hall. They shared assemblies and the Belgians were taught English while the Malvern pupils began learning French.

Malvern College played a significant part in the war effort, both in Malvern and on the front. A total of 2,833 former college pupils are known to have served in the war, and 459 died. Some had grown up in Malvern and were sons of college staff, such as Major Stanley Colt Faber, killed in 1917.

Students were encouraged to offer their free time digging the gardens of families whose main breadwinner was away fighting. A letter from a college master written in 1917 has come to light stating that the boys' cricket ground would soon be turned into a vegetable patch to provide more food.

Help from school children was sought by the government. The Ministry of National Service appealed in 1918 for pupils to be released during term time to bring in hay, corn and potato crops. Children were also required to gather wild blackberries to supplement fruit harvests used to make jam for the troops.

Malvern farmers were not too happy about children e trespassing on their fields though. Local schools were involved in collecting fruit stones and nut shells which were burned to make charcoal filters for gas masks. Chestnuts were also gathered in by the tons since they produced acetone necessary to manufacture cordite for use in artillery shells.

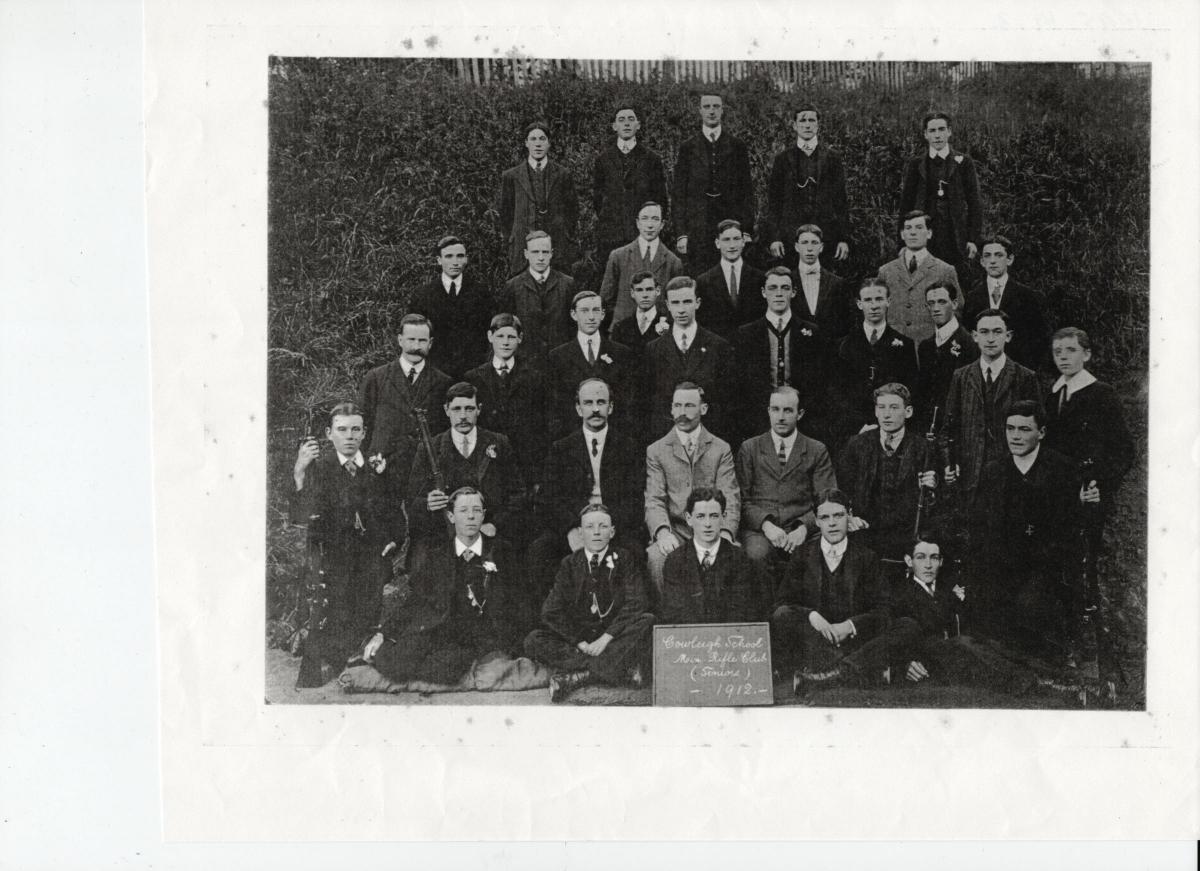

By the end of the war, great concern was expressed concerning the malnourishment of many Malvern children. Communal kitchens were set up to support pupils at North Malvern and Cowleigh schools, and other kitchens followed in Barnards Green and Malvern Link.

Miss Severn Burrow wrote to the Malvern Food Control committee thanking them for supplying additional milk to the delicate girls at the open-air school in West Malvern.

She said that the average weekly weight gain per child had risen to 1¼ lbs as a result. Other schools reported similar health benefits as a result of the free school meals.

Information has been taken from Malvern Gazettes published during the war. Three publications on Malvern in the Great War are available from Malvern Museum.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here